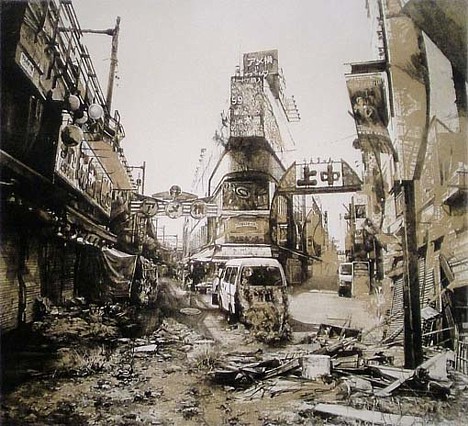

Post-Apocalypse

One of the chapters of my monograph, Fictions of the Not Yet: Time and the 21st Century British Novel, explores the genre of post-apocalypse through a reading of Ernst Bloch's philosophy of "natural historical time." Many critics have commented upon the wave of SF and (post-)apocalyptic novels over the last decade authored by award-winning, “literary” writers across Britain, North America and Europe. This apparent vogue for disaster narratives might therefore be said to disclose an aesthetic index of the escalating perceived likelihood of ecological disaster. However, several recent novels of eco-catastrophe – Sam Taylor’s The Island at the End of the World (2009), Maggie Gee’s The Flood (2004), Jeanette Winterson’s The Stone Gods (2007) and Jim Crace’s The Pesthouse (2007), for instance – reject the “hard-edged naturalism” we might expect to find in apocalyptic fictions. Instead, these novels offer a variety of positively-inscribed, natural – and post-human – futurities, posing some important questions for twenty-first apocalyptic narratives: what kind of “Arcadian revenge” (if any) is being constructed in fictions of ecological catastrophe? And, more specifically, how can aesthetic representations of apocalypse speak to contemporary debates concerning co-evolution, the discourse of limits, and impending ecoscarcities?

Rather than the brutal naturalism we associate with British apocalyptic fictions in its “classic” phase during the 1950s, we find ourselves confronted in texts like The Pesthouse and The Flood with verdant – even, at times, benevolent – (post-)apocalyptic landscapes whose manifest distance from darkly dystopian depictions of mushroom clouds and brute survivalism appear to owe more to early “New Wave” natural disaster fictions than to the technologically-driven apocalyptic visions of the 1980s and 1990s. It is my argument that this particular caucus of British writers are using the genre of (post-)apocalypse, then, to offer chronotopically-organised representational locales through which we discover times that function both within and outside of historical time – responding to the question, as Steven Connor notes, “of how we are to live in and out of history.” These innovative narrative times can usefully be considered through the concept of Ungleichzeitigkeit (“non-contemporaneity”) that the German utopian philosopher Ernst Bloch developed in his analysis of fascism.

See also my article on Sam Taylor's fiction, "Rethinking the Arcadian Revenge: Metachronous Times in the Fiction of Sam Tyalor."

Dr Caroline Edwards is Senior Lecturer in Modern & Contemporary Literature at Birkbeck, University of London. Her research and teaching specialisms are in 21st century literature and critical theory, science fiction and post-apocalyptic narratives, Marxist aesthetics, and utopianism.

Dr Caroline Edwards is Senior Lecturer in Modern & Contemporary Literature at Birkbeck, University of London. Her research and teaching specialisms are in 21st century literature and critical theory, science fiction and post-apocalyptic narratives, Marxist aesthetics, and utopianism.

Follow / Contact