Economic SF

The economics magazine STIR hosted a panel discussion on “Economic Science Fictions” to celebrate the launch of its Autumn 2018 issue on “Co-operating out of Crisis.” I was pleased to be ask to contribute with a short talk on “The Economics of Nowhere” which considered how the genre of the literary utopia is particularly well suited to denaturalising conventional economic theory and imagining alternative economic paradigms. Since the critique of capital accumulation in Thomas More’s Utopia (1516), utopian narratives have considered the value of money as a social technology and whether its abolition might furnish a more equitable sharing or commoning of resources. In Utopia, the entanglement of money, indebtedness and inequality is seen as the prime originator of poverty and crime, and establishes one of the defining characteristics of utopian narratives from More’s 1516 text onwards. Utopian literature, then, privileges the following:

- Abolition of money – removal of inequality and necessity of crime, leads to peace, stability and no need for crime and punishment

- Abolition of private property & nationalisation – socialist politics of collective ownership, state education, nationalised hospitals, roads etc.

- Leisure made possible by automation – releases citizens into various forms of pleasurable cognitive and aesthetic labour

- End of scarcity – utopian visions of future and alternate worlds tend to imagine post-scarcity societies – achieved through a combination of socialist politics of collective ownership, ideas borrowed from the co-operative movement and communitarianism, as well as fantasies of abundant energy and advanced technologies

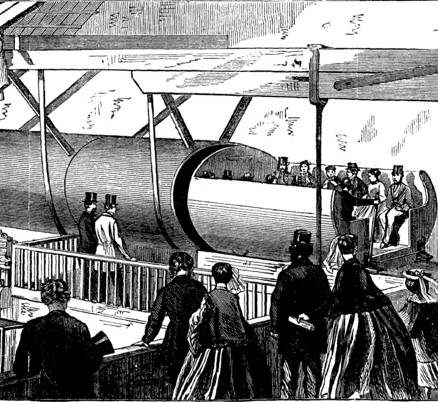

In the talk I asked wehether the dream of full automation in late-19th century utopian narratives might be relevant for our own 21st-century moment of economic disruption. The question of full automation animated socialist discourse in the late 19th century and is the prerequisite for achieving a leisured way of life in the majority of utopian novels of the period – as can be seen, for example, in Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward, 2000–1887 (1888), Mary Griffith’s earlier euchronian novella Three Hundred Years Hence (1836) and Mary E. Bradley Lane’s separatist hollow-earth utopia, Mizora: A World of Women (1880-1).

The dream of full automation in these early science fictional texts doesn’t always deliver a utopian future and can be seen as the driver of early dystopian fears about mechanisation and its effects on subjectivity. As Émile Souvestre suggested in his earlier dystopian adventure narrative Le Monde tel qu’il sera [The World As It Shall Be] (1846), highly technologised futures could just as easily deliver a world of complete commodification in which all citizens are transformed into money-grubbing entrepreneurs seeking ever-new ways of extracting profit from their unsuspecting neighbours; and lunar colonisation simply opens up a new frontier for accumulation. Anna Bowman Dodd’s epistolary novella The Republic of the Future; or, Socialism a Reality (1887) similarly imagines a fully mechanised American future in the mid-twenty-first-century.

Three recent studies have returned to this earlier dream of full automation at a time of self-driving cars, computerised manufacturing, fully automated factories, nursing-care robots, and the replacement of white collar jobs like legal services by automation. Paul Mason’s Postcapitalism: A Guide to Our Future (London: Penguin, 2016), Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams’ Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work, revised edition (London: Verso, 2016) and Aaron Bastani’s Fully Automated Luxury Communism: A Manifesto (London: Verso, 2019) suggest that a very different political and economic system can now finally be achieved.

The talk concluded by suggesting that at a time when it is all to easy to forge extrapolations of the future that are inescapably dystopian, it’s worth returning to earlier utopian and socialist narratives of the science fictional future – when rather than becoming the instruments of complex financial circulation and exchange, machines delivered post-scarcity visions of leisure and equality.

Also on the panel were James Pockson from PostRational and Dan Gavshon-Brady from Wolff Olins, Prof. Caroline Basset (University of Sussex), and afrofuturist author Florence Okoye (who also works at the Natural History Museum in her day job).

You can preview the slides that accompanied my talk below, or click on the SlideShare link to view.

Dr Caroline Edwards is Senior Lecturer in Modern & Contemporary Literature at Birkbeck, University of London. Her research and teaching specialisms are in 21st century literature and critical theory, science fiction and post-apocalyptic narratives, Marxist aesthetics, and utopianism.

Dr Caroline Edwards is Senior Lecturer in Modern & Contemporary Literature at Birkbeck, University of London. Her research and teaching specialisms are in 21st century literature and critical theory, science fiction and post-apocalyptic narratives, Marxist aesthetics, and utopianism.

Follow / Contact